Babies Are Dying in the Developing World for Lack of Breastfeeding. What’s the Effect on Infants in Developed Countries?

Figures from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) spell out the terrible toll taken on infants in some poorer countries. Even in a large and rapidly developing country such as Nigeria, more than one in ten babies do not make it to their fifth birthday.

Nigeria has halved its child mortality rate since 1990; before that twenty-one percent of children died before they were five. The figures are similar to those for other west African nations such as Chad and the Central African Republic. UNICEF says that despite the steep decline in child mortality an estimated 5.2 million children under five died across the world in 2019.

UNICEF blames poor nutrition, among other factors, for placing many of such countries’ youngest citizens in so much danger, and has highlighted breastfeeding as a critical part of the solution. The role of malnutrition in damaging infant health is borne out by the high proportion of under-fives who are medically considered to be stunted in their growth in poor countries – more than four in every ten in Nigeria for example.

The same poor nutrition that leads to stunting also makes children vulnerable to infection, and in Nigeria’s case contributes to the loss of 2,300 infants under five every day. Malnutrition rates are gradually improving – at an average of just over three percent according to UNICEF – but this painfully slow progress is leaving many of the youngest in acute danger.

How are developed countries doing by comparison? According to UNICEF figures from 2019, in the United States 6.5 children in every thousand born died before their fifth birthday; in Canada it was 4.9 per thousand, in the United Kingdom 4.3, Sweden 2.6, and Norway 2.4.

Different conditions across countries make it hard to isolate particular reasons for child mortality, but it’s clear that given its status as one of the most medically advanced and richest countries in the world the United States performs poorly in protecting the lives of under-fives.

Unequal access to health care has left a sizable minority of the population vulnerable, despite government programs designed to cover children of poor families. But diet, and perhaps even rates of breastfeeding, seem likely to be part of the equation.

Certainly the Federal Government, and professional bodies such as the American Academy of Pediatrics want more babies to be breastfed, and for longer. Although it falls a long way short of proving cause and effect the figures for breastfeeding are lowest in the states – such as Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Arkansas – with the highest rates of mortality among children aged under five.

The Federal Government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that babies be fed exclusively on breast milk for the first six months of their lives, and continue to be breastfed up to their first birthday as complementary foods are gradually included in their diet. The law – introduced only recently as part of the Affordable Care Act – requires that nursing mothers be given “reasonable breaks” at places of work in order to express milk.

What is so special and important about breastfeeding?

The answer appears to lie in the particular need of babies for a special diet that’s evolved with humans to give them the best chance of longer-term survival.

The mix of ingredients unique to human breast milk, and so far never replicated by any commercial formula, has been shown by many scientific studies to confer on babies, long term benefits in physical development and resistance to disease.

There’s evidence from research in India – comparing babies who were breastfed with others who were not – of significant protection against neonatal illnesses. The longer, and more exclusively, a baby in the study was breastfed, the greater the protection.

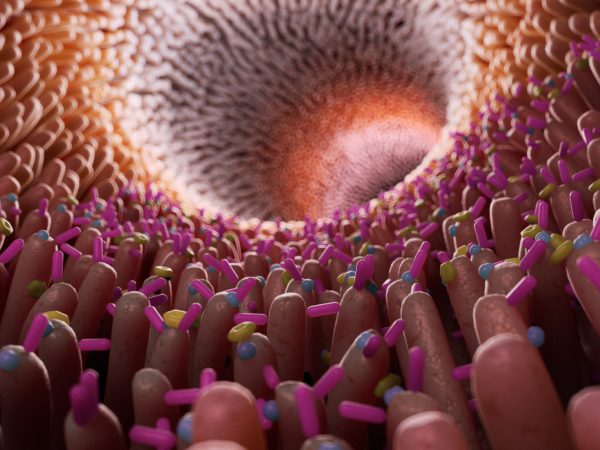

This protection seems to come partly through growth factors and anti-bodies called immunoglobins contained in breast milk that guard the infant gut and “educate” the immune system about what can be tolerated and what must be attacked. The nutrients in breast milk change over the course of lactation, even over the course of a day or a single feed, and are ideally suited to human babies.

Particular species of bacteria contribute to the development and maintenance of a healthy immune system, and breast milk has been found to contain the “prebiotic” carbohydrate galacto-oligosaccharide, a soluble dietary fiber well suited to nurture such bacteria.

A telling example of the way breast milk is matched to babies is its markedly lower protein content, as compared to cow’s milk. Human milk is designed to “grow” a small baby whereas that of a cow has to allow a much bigger animal to develop, and to do so far more quickly.

Research into the impact of breast milk on children’s health has shown that it reduces infections of the gut and the middle ear, illnesses commonly found in infants. One study found that breastfeeding for more than three months reduced the risk of Type 1 diabetes, a disease thought to be caused by the immune system attacking the body itself. Similarly, breastfeeding is associated with a reduction in other “autoimmune” diseases.

Breastfeeding also appears to benefit mothers, helping the body to recover from giving birth, and making premature conception of another child much less likely. Studies have found an array of benefits to the longer-term health of mothers including improvements in blood pressure and the way fat is burnt as fuel, and a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease, and breast and ovarian cancer.

There’s even evidence that breastfed babies turn out to be more clever. A study in 2013 found that babies had higher IQs at the age of 3 and 7, in proportion to the duration of breastfeeding.

The duration of breastfeeding is a critical issue, and international bodies such as UNICEF continue to urge mothers in the developing and the developed world alike to feed exclusively for six months before gradually introducing solid food. One clear advantage is that the longer a baby is breastfed, the longer he or she will be protected from waterborne disease, one of the chief causes of infant mortality. The baby will also inherit some of the immunity from infection that his or her mother has developed as a result of encountering pathogens that might have proved deadly to a baby.

Conditions are different in the United States, and the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (the CDC) highlights other benefits of breastfeeding, reductions in the risk of asthma, obesity, type 1 diabetes, ear and gastrointestinal infections and sudden infant death syndrome.

But governments and international agencies alike have found it hard to achieve higher rates of breastfeeding. The CDC says that although 84 percent of American babies got their first nutrition from their mother’s milk, only 58 percent of them were still breastfeeding six months later. Almost one in five of the babies born in 2017 who were being breastfed was also receiving infant formula before they were two days old.

It’s a similar story in Nigeria. UNICEF is promoting the “breast is best” message alongside its “Every Child Alive” campaign to reduce death among newborn children in Nigeria. But the proportion of Nigerian mothers who breastfeed exclusively has not increased over the last ten years, and barely a quarter of babies are fed on human milk alone for the first six months. It’s likely that low rates of breastfeeding contribute to what UNICEF says is fewer than one in five Nigerian infants aged between 6 and 23 months being fed the “minimum acceptable” diet. An estimated 2.5 million children in the country are considered “severely malnourished”.

As distinct from industrialized countries, part of the problem in Nigeria lies in wider malnutrition. Among women of childbearing age, seven percent are acutely malnourished. That undermines their ability to provide milk for their baby. Maternal malnutrition is also likely to be worst among the poorest populations where breastfeeding has the most impact on infant health.

Nigeria cannot afford to ignore malnutrition. It contributes to the cost of providing health care. Stunted children may be undeveloped in their mental abilities as well as their physical growth, undermining their education and leading to lower economic productivity. UNICEF estimates that stunting costs Nigeria up to eleven per cent of its Gross Domestic Product.

In parts of Nigeria, the need for women to get back to work, and the lack of facilities for breastfeeding or expressing breast milk to feed to their babies later, help to the practice. So does the availability of baby milk formulas, even though none of them replicates the blend of ingredients and immune protection offered by mothers themselves. Some mothers cannot feed their babies and are glad to have access to the manufactured alternative. They’re all problems shared to a greater or lesser extent by many women in the United States.

However, in contrast with the immediate problem of malnutrition facing children in countries such as Nigeria, obesity threatens the long-term health of many American children. Weight gain that is too rapid in babies is associated with obesity in infancy and childhood, and is a risk factor for obesity in later life. Studies on the subject have produced varying results, but have tended, albeit inconsistently, to associate increased breastfeeding with a lower risk of obesity.

One relatively recent study – published in the journal Pediatrics in 2018 – found that in 2,500 mother-baby pairs that the more babies were breastfed the less quickly they grew and the lower their later risk of obesity. The greatest benefit went to babies who had breast milk exclusively for at least three months.

Although the study showed a “dose-dependent” relationship – that is, the more feeding was of breastmilk the greater was the effect – it was an “association” rather than proof of cause and effect. Breastfeeding is potentially controversial, because, despite the reported benefits, mothers do not want to be judged by others or feel placed under a moral obligation to feed their babies in this way, especially exclusively.

It’s easy for studies to overlook other factors among breastfeeding mothers that could be acting against obesity. Figures suggest that mothers who choose breastfeeding, especially those who can afford to do so exclusively for three months, are more highly educated, have higher incomes and can provide a better supplementary diet as the child grows older.

But independently of the circumstances in which babies are raised, enough is known about the composition of breast milk to support a connection with good health – including avoiding obesity. Just as ingredients in it appear to support the sort of bacteria that act against infection, so they support bacteria that reduce the risk of obesity.

The 2018 study provided an interesting footnote: the greatest protection against obesity was among babies fed directly from the breast rather than with expressed milk from a bottle. It seems that’s at least partly the result of parents encouraging babies to finish the bottle whereas at the breast they might have stopped sucking when they felt full.

The American Academy of Pediatrics – aware that knowing when you’ve had enough is a critical skill in avoiding obesity – recommends what it calls “responsive feeding”. It shows that even if “breast is best”, it’s possible to have slightly too much of a good thing.